in the East many are read from right to left or vertically, in

columns.

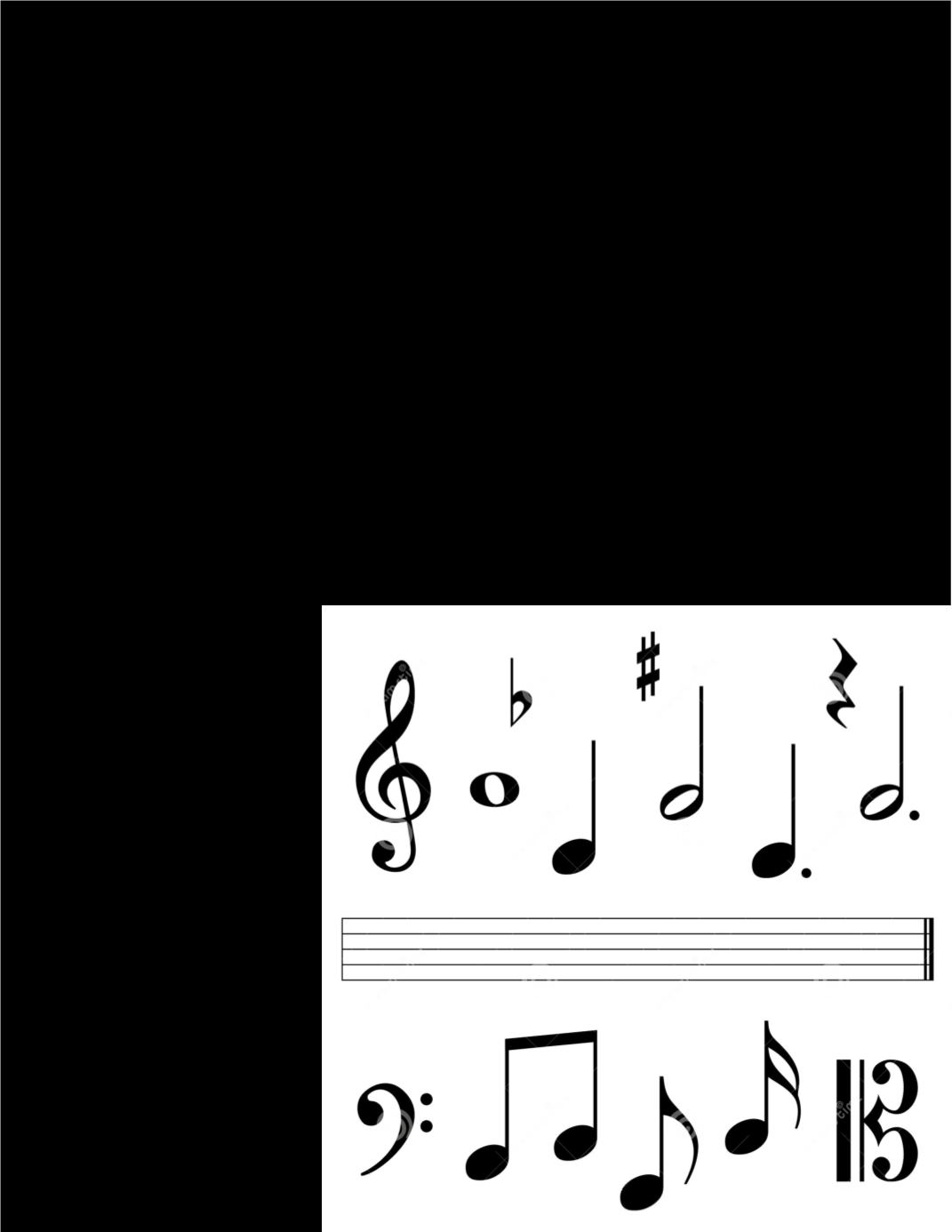

A second fundamental distinction is that between rep-

resentational notations, which depict the sound of the

music—leaving the player to produce that sound as he

or she wishes—and tablatures, which instruct a player as

to the technical means of producing a sound. Phonetic

symbols play an important role in both types of notation,

while graphic signs contribute mainly to representational

notations. A prime example of non-Western representa-

tional notation is the kraton notation used in music for the

Javanese gamelan orchestra, its grid using the “graph”

principle found also in Western staff notation but oriented

at a 90° angle relative to the latter.

Verbal and syllabic notations

In oral traditions of music, solmization (the naming of

each degree of a basic scale with a word or syllable) is

important. The modern European sol-fa method (“do,”

“re,” “mi,” etc.) is such a system. The Indian syllables ṣa,

ṛi, ga, ma, pa, dha, ni are similar, as are the Balinese ding,

dong, deng, dung, dang; the ancient five-note Chinese

scale kung, shang, chiao, chih, yü; and the Korean tŏng,

tung, tang, tong, ting; and rŏ, ru, ra, ro, ri (the two sets be-

ing used for different instruments).

Slightly different are the 12 chro-

matic Chinese lü; syllables: each

pitch bears the name of a bell—as

huang chung (“yellow bell”), ling

chung (“forest bell”)—and its name

is reduced to a syllable—huang,

ling, t’ai, etc. Though primarily for

reciting or singing as a melody is

being learned, these syllables can

be used to write down the notes of

a melodic line (each appearing as

a single ideogram in the Chinese

examples) and thus form a simple

syllabic pitch notation. Of the five

Balinese syllables, only their vowels

are used in written form—i, o, e, u,

a—so that a letter notation results;

this is still an abbreviated syllabic

notation, not an alphabetical one.

In Western plainchant, abbreviated

words were used to indicate duration

(for example, c = cito or celeriter =

“short” value) and direction of me-

lodic movement (l = levare, and s =

sursum = “upward”). In the notation

of early Ethiopian church music

a single letter or a pair of letters

(short for a passage of text) signified

a group of notes, even a complete melodic phrase. The

drum syllables of North Indian music are a solmization of

timbre (as na, ta, dhin) and often also of rhythmic patterns

(as tirikita, dhagina) and can be written down to make a

notation.

Alphabetical notations

Alphabets are historically a phenomenon of the Middle

East, Europe, and the Indian subcontinent. Their ordering

of letters provides a convenient reference system for the

notes of musical scales in ascending or descending order.

Alphabetical notations are among the most ancient mu-

sical scripts. Two Greek notations were of this type, the

earlier using an archaic alphabet and the latter using the

Classical Greek alphabet. Many comparable notations

arose in the Middle Ages, and the modern note names, A

to G, are an outgrowth of these.

The clefs of staff notations are a formalized survival. The

system of pitch notation devised by 19th-century German

philosopher and scientist Hermann von Helmholtz was

derived from the Greek system, using dashes for octave

register but employing Roman letters: A{sub double

prime}, B{sub double prime}, C{sub double prime}–B{-

sub double prime}, C–B, c–b, c′ (middle C)–b′, c″–b″,